Case Report - (2023) Volume 8, Issue 12

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Pstd) and Intellectual Disability (Id): A Litera-ture Review on Dual Diagnosis and Case Study Presenting Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (Fasd)

2Center of Psychotraumatology and Mediation (CPM), Neuchatel, Switzerland Institute of Psychotraumatology and Mediation, Neuchâtel, affiliated to SIFM: Swiss Institute for Medical Postgraduate and Continuing Educ, Switzerland

3Department of Medicine, Ottawa Hospital, Riverside Site, Rheumatologist and Clinician Investigator at The Ottawa Hospital’s Division of Rheumatology. Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, The Ottawa Hos, Canada

4Counselling and Spirituality, University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, CPM: Centre for Psychotraumatology and Mediation, Ottawa, O, Canada

5Mental Health Research Branch, Knowledge Institute, Montfort Hospital, Ottawa, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, ON, Canada

6Department of Psychiatry, Mental Health Program, Montfort Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, ON, Canada

Received Date: Dec 07, 2023 / Accepted Date: Dec 19, 2023 / Published Date: Dec 25, 2023

Copyright: ©2023 Issack BIYONG, et al. This is an open-access ar-ticle distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited.

Citation: BIYONG, I., Maltez, N., Ngo Begue, I.C., Tempier, R., & Ducharme, R. (2023). Sarcoidosis: Incidental Finding in Acute Renal Failure, Hypercalcemia, and Elevated Angiotensin Converting Enzyme. J Clin Rev Case Rep, 8(12), 305-312.

Abstract

This article focuses on a detailed case study of a 36-year-old female with a dual diagnosis combining intellectual disability and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The interest of this case is to show the complexity of differential diagnosis and biopsychosocial therapeutic management in this type of patient.

The patient underwent a thorough psychiatric evaluation using psychometric scales, leading to the diagnosis of PTSD with psychotic symptoms comorbid with generalized anxiety and depression, against a background of moderate to severe intellectual disability. Multimodal treatment combining pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT and EMDR) and psychosocial intervention was instituted over several months, leading to a marked improvement in symptoms as assessed by follow-up psychometric evaluations. This case illustrates the need for a high level of diagnostic suspicion and specialized interdisciplinary care for this population vulnerable to trauma and mental disorders.

Keywords

Dual diagnosis, Intellectual disability, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Psychotic symptoms, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

Introduction

The term “dual diagnosis” refers to the co-occurrence of an intellectual disability and a psychiatric disorder in the same patient [1]. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the intellectually disabled population is said to be 2 to 3 times higher than in the general population [2].

Several factors contribute to this increased vulnerability to mental disorders. On the one hand, certain etiologies at the origin of intellectual disability, such as chromosomal or genetic abnormalities, early encephalopathies, or prenatal exposure to alcohol or toxic substances, also predispose to the development of psychopathologies [3].

On the other hand, the cognitive limitations inherent in intellectual disability, in particular difficulties in verbal and emotional communication, complicate symptomatic expression and the identification of emerging psychiatric disorders by family and caregivers [4]. This is why it is so important to take into account the needs of the patient.

The differential diagnosis between disability-related behavioral manifestations and genuine comorbid mental disorders therefore remains complex. This often leads to delays in specific treatment. Several studies have highlighted the lack of adequate training for healthcare professionals in dual diagnosis, which contributes to significant delays in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness in this population [3].

However, screening, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of co-morbid psychiatric pathologies in people with intellectual disabilities are crucial to their overall health and psychosocial quality of life [4].

Method

This is a clinical case study describing in detail the psychiatric evaluation of a 36-year-old female patient admitted to the emergency department and subsequently referred as an outpatient to a specialist treatment clinic. The assessment includes a thorough history, a qualitative and quantitative psychometric assessment, and the formulation of a diagnosis and personalized treatment plan.

This case study is of great interest due to the complexity and peculiarities of the clinical picture. Indeed, the patient presented a rare comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and intellectual disability, also known as “dual diagnosis”. The simultaneous presence of these two pathologies poses numerous diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, hence the need for specific expertise [5].

The aim of this paper was therefore to outline the detailed psychiatric assessment process that led to the diagnosis of dual diagnosis in this patient, as well as the adapted multimodal therapeutic management that followed. Emphasis is placed on the targeted use of questionnaires and psychometric scales to objectivize symptoms and their intensity, make the diagnosis and monitor the patient’s progress and symptoms throughout the treatment plan.

Procedure

An initial assessment of psychiatric symptoms was carried out using questionnaires and validated psychometric scales such as the PCLS-5, HAS and IDB. These standardized tools also enabled quantitative monitoring of the evolution of disorders throughout the treatment.

The therapeutic approach is based on a biopsychosocial model that takes into account the multidimensionality and complexity of the dual diagnosis:

Psychoeducation: In-depth psychoeducation sessions were provided to improve the patient’s knowledge and introspection about her disorders, reinforce her therapeutic adherence, and explain the mechanisms of action of the medication and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) treatments envisaged, in particular the eye movement desensitization technique (EMDR).

CBT and EMDR: The combination of CBT and EMDR focused specifically on post-traumatic symptomatology and associated cognitive distortions. Repeated use of this technique during sessions enabled progressive desensitization to traumatic memories with positive conditioning, leading to a significant reduction in PTSD-related reliving and ruminations.

Psychosocial treatment: Close coordination with community medical and social services has been achieved to support family and friends, and to set up discussion groups for caregivers of people with a combination of intellectual disability and psychiatric disorders.

Our Clinical Case Study

4.1 Identification and Reason for Consultation

This is a 36-year-old Caucasian woman living with her mother. She is single, childless and unemployed. Her mother accompanies her and is present at the interview to complete the information. The patient presents voluntarily to the emergency department for persistent auditory hallucinations that are becoming increasingly intense.

4.2 History of Current Illness

The patient reports hearing women’s voices constantly, speaking directly to her and commanding her. They ask her to cut and hit herself. What’s more, these voices insist that the patient hurt others around her. At the time of the interview, they told her to hurt the psychiatrist and break a mirror. At the same time, she reports being able to ignore them and not act. The patient has great difficulty sleeping. She has many nightmares that frighten her and prevent her from falling asleep and staying asleep. She describes a recurring dream of a woman in her sixties falling from a building. This dream is repeated very often, and it’s always the same woman. The patient has recently fallen while walking and fears it will happen again. She reports visual hallucinations. She reports seeing another lady in the room, this woman has long hair and follows the patient around. However, when the patient asks her to leave, the woman disappears through the ceiling.

The patient has been feeling very sad and anxious lately. She fears dying, becoming very fat and falling. She has intermittent somatic symptoms of the anxiety series, including sweating, palpitations and sometimes even dizziness. Her mother noted no obsessions or repetitive behaviours. However, the patient often has “fits of nerves”, becoming very impatient and shouting when frustrated. As a child, she would have several outbursts and was very often aggressive. As a child, the patient suffered a lot of “taxing” or harassment at school. Other children would call her names, push her around, pull her hair and even lift her skirt. The patient remembers all these events and can describe them in detail. She also recounts a time when she got frustrated at school and pushed another student into a metal locker room, resulting in a serious head injury. The patient also reported that she had once been the victim of rape, and this was confirmed by her mother, but without much elaboration due to feelings of embarrassment and guilt. The patient has “Flashbacks” and nightmares very often. She’s also afraid of “having schizophrenia” like her mother. She describes how she hears voices like her mother, who is known to have schizophrenia. She also tells us about her intellectual disability. The patient has a very sedentary lifestyle and watches a lot of television.

4.3 Psychiatric History

The patient has been under psychiatric care for five years, mainly due to anxiety-related symptoms and episodes described as “nervous breakdowns”. No history of hospitalization for psychiatric disorders has been recorded during this period. The particularity of her profile lies in her intellectual disability, assessed as moderate to severe, with an IQ of 20-25 | 50-55, according to DSM-5 criteria [6]. This intellectual disability is attributed, in accordance with these references, to his mother’s consumption of alcohol during pregnancy. It should also be noted that the patient has a complex family history, with a mother diagnosed with schizophrenia and several family members with a history of mental disorders, as recorded in various studies [7].

4.4 Medical and Surgical History

According to the patient, she had intestinal ischemia in 2005. In addition, she underwent a cholecystectomy for lithiasis and a hysterectomy for heavy bleeding. She has a history of congenital heart defects such as Tetralogy of Fallot, Transposition of the great vessels and valvular anomalies, diagnosed and treated since birth. She also has a history of deep-vein thrombosis.

However, she does not know the details of her previous treatment and follow-up.

4.5 Medications, Habits and Allergies

The prescribed oral medications are as follows: Citalopram 20mg, Rabeprazole sodium 20mg, Docusate Sodium 20mg, Warfarin 4mg, Metoclopramide 10mg, folic acid 5mg, Metoprolol 50mg, Sennosides A&B 8,6mg, Risperidone 3mg [8]. The patient reports good compliance with medication. She uses a dosette supplied by the pharmacy. She denies any use of tobacco, alcohol or illicit drugs. She has a very sedentary lifestyle and a very good appetite. She is trying to lose weight, but without success. She has no known drug, food or environmental allergies.

5. Mental Examination

The patient looks her age. Her clothing is clean and appropriate for the season. Body and clothing hygiene are moderately maintained. The gaze is sometimes fixed and rather distant. The patient is alert throughout the interview. She is oriented and not confused.

She shows no agitation or psychomotor slowing. Tone and rhythm of speech are appropriate. She often uses repetitive sounds and repeats words or phrases when trying to express ideas. Mood is sad and anxious. Affect seems congruent and reactive. Thinking is illogical, with magical thoughts such as ‘a woman disappearing through the ceiling’. Auditory and visual hallucinations (see history of current illness). Judgment and selfcriticism are limited. The patient was nevertheless able to realize that the auditory hallucinations were not normal, and came to the emergency room accompanied by her mother.

6. MULTIAXIAL Diagnosis According To DSM-5

6.1 Axis1: Emotional and behavioral disorders

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic symptoms Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with psychotic symptoms

6.2 Axis2: Personality disorders and intellectual disabilities

- Moderate to severe intellectual disability (IQ: 20-25 | 50-55); secondary to alcohol consumption during pregnancy (fetal alcohol syndrome) was documented in her file in the hospital archives.

6.3 Axis3: Medical conditions - Congenital heart defects such as Tetralogy of Fallot.

- Transposition of blood vessels and valvular anomalies diagnosed and treated since birth. She also has a history of deep vein thrombosis.

6.4 Axis4: Psychosocial and environmental stressors

- Mother with schizophrenia, harassment at school, awareness of intellectual disability, head injury, rape.

6.5 Axis5: Global Scale of Functioning

- EGF is estimated at 60 at the treatment and 85 at the end.

During the interview, the patient describes traumatic events in her past. In particular, she had suffered harassment or bullying at school, and she acknowledges that she has an intellectual disability, which is traumatic in itself. In addition, the patient is aware that her disability is attributable to alcohol consumption during pregnancy, probably leading to fetal alcohol syndrome. This can have a significant effect on the mother-child relationship. She has severe nightmares and flashbacks, in addition to psychotic symptoms. The patient isolates herself socially and has no interest in activities. She has frequent seizures and significant behavioral changes. She has difficulty sleeping and is always very alert. The “nervous breakdowns” seem to illustrate exaggerated reactions. All these symptoms have persisted for over a month. The patient therefore meets the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder according to DSM-5 (2013).

In addition, the patient recounts several situations in which she feels very anxious. She fears falling, becoming fat, etc. According to collateral information, these symptoms have persisted since childhood. We can therefore conclude that the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder according to DSM-5 (2013) are also present.

7. Treatment Plan

The treatment plan was developed by our multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, medical students and family medicine residents, as part of a psychiatry rotation at the University of Ottawa.

7.1 Psychopharmacological treatment

1. Extended-release Topiramate, started at 25mg and increased to 50mg morning and evening after 7 days, with the aim of reducing PTSD-related reliving and nightmares. Dosage was then gradually titrated up to 200mg/day on an outpatient basis.

2. Escitalopram 10mg increased to 20mg in the morning after one week, to treat comorbid depressive and generalized anxiety symptoms.

3. Risperidone, whose initial dosage of 6mg/day since admission to the emergency department has been reduced to 3mg/day on an outpatient basis. This atypical antipsychotic stabilizes mood and improves cognitive and behavioral disturbances frequently associated with the dual diagnosis of intellectual disability and PTSD.

4. Continuation of existing background treatment, in combination with outpatient cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and EMDR.

7.2 Psychological treatment

We combined the EMDR technique with brief CBT, in parallel with pharmacological treatment. Before initiating psychotherapy and EMDR, a quantitative psychometric assessment was carried out using the PCLS-5 (Weiss et al., 2010), HADS [9] and BDI-II [10] scales, and repeated during and after treatment to objectivize symptomatic evolution. EMDR + CBT treatment took place over 3 months, with 4 sessions per month in the first month, 4 sessions in the second month and 2 sessions in the third month, for a total of 10 sessions. During the consolidation phase, family psychoeducation sessions and coordination with the Ontario Provincial Dual Diagnosis Network [10] were implemented.

7.3 Psychosocial treatment

By collaborating and coordinating with appropriate and effective networks of specialized cross- sectoral services to support the family. This synergistic work makes it possible to include in psychosocial support groups families of people with intellectual disabilities who need high levels of support and complex care, as in our case study.

Community Networks of Specialized Care (CNSC) represent a new way of bringing together specialized services and professionals in Ontario. They pool their expertise to help and support adults with developmental disabilities and mental health needs and/or behavioural disorders (i.e., dual diagnosis) in the communities where they live. Networks bring together people from a variety of sectors, including developmental services, health, research, education and justice with a common goal of improving coordination, access and quality of services for these individuals with complex needs [11]. We transferred him to the family doctor for a prescription of psychotropic drugs such as: Sertraline 100mg (1-0-0-0) for his depression and PTSD and Topiramate 50mg (1-0-0-1) for PTSD acting on nightmares and flashbacks which helped him a lot with a weight loss of 5kg in 3 months [18]. Risperidone 3mg was continued at the end of treatment for continuous evening administration, indicated for behavioral disorders in the mentally retarded, sleep disorders and disorders secondary to Trauma and Psychosis [8].

We kept in touch with the family doctor if necessary, and were instructed not to change medication without a psychiatric consultation in our outpatient unit at the Trauma Clinic and Transcultural Psychiatry (CTPT), Mental Health Program and also the Mental Health Care for the Mentally Impaired outpatient unit. Montfort Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario.

Results

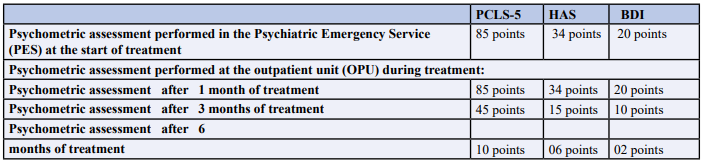

Table 1: Psychometric Assessments

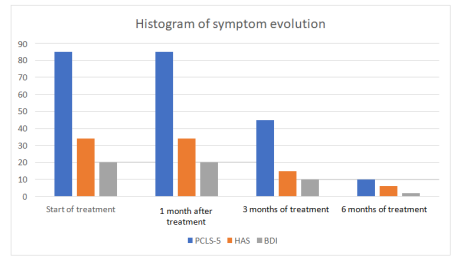

Figure 1: Histograms showing the evolution of symptoms during treatment

In-depth analysis of the psychometric data suggests a positive evolution of the patient’s symptoms throughout treatment. High initial scores on the PCLS-5 (Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist), HAS (Hamilton Anxiety Scale), and BDI (Beck Depression Inventory) indicate a significant presence of posttraumatic stress symptoms, anxiety and depression.

At the start of treatment, the patient presented high levels of psychological distress, as evidenced by high scores on all scales. However, from the first month of treatment in the Out Patient Unit (OPU), scores remained relatively stable, perhaps suggesting an initial stabilization of symptoms.

Real improvement becomes apparent after three months of treatment, when significant reductions are observed on all scales. This reduction in scores was maintained and intensified after six months of treatment. The PCLS-5 fell from 85 to 10 points, the HAS from 34 to 6 points, and the BDI from 20 to 2 points.

8.1 Score interpretation

PCLS-5 (Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist): The drastic reduction in scores from 85 to 10 points suggests a substantial improvement in post-traumatic stress symptoms. Treatment appears to have a positive impact on the management of these symptoms.

8.2 HAS (Hamilton Anxiety Scale)

Lower scores on the anxiety scale from 34 to 6 points indicate a significant improvement in the patient’s anxiety state. This can translate into a better quality of life and more stable day-to-day functioning.

8.3 BDI (Beck Depression Inventory)

The reduction in BDI scores from 20 to 2 points indicates a drastic reduction in depressive symptoms. Treatment appears to be effective in managing associated depression as comorbidity to PTSD.

The positive evolution of scores on the various psychometric scales suggests that the treatment was beneficial for the patient. However, it is important to continue to monitor the patient closely, adjust the treatment plan as necessary, and explore the factors contributing to this improvement. Continued collaboration with the medical and psychosocial care team in the community, follow- ups at the OPU, Mental health program and Department of Psychiatry is essential to maintain this progress and ensure the long-term well-being of this patient, as confirmed by the aforementioned results.

Discussion

Cases of dual diagnosis involving Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder are particularly common [12]. These patients are at high risk of abuse. They have a limited capacity for social support. They are also often hospitalized as children, which can disrupt family relationships [13]. Finally, recognizing that you yourself have an intellectual disability, that you are not like others and that you will always be dependent on others is a traumatic realization in itself [12].

The cases of patients with a history of psychological trauma and psychoses [13] and a picture of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with psychotic symptoms are widely documented in the psychiatric literature.

Assessing these patients requires an interview adapted to their specific needs. Choose an effective means of communication and be alert to any behaviors, mentions or anecdotes recounted by the patient. The possibility of signs and symptoms such as aggressive behavior, rage, self-mutilation, lack of compliance, social isolation, insomnia, etc., must also be considered [12]. Another obstacle is the lack of diagnostic tools.

A scale adapted to patients with intellectual disabilities was developed by Tomasulo et al (2016). This scale creation was used as a basis in the criteria from the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) to develop an effective tool for the dual diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and intellectual disability. For example, the criterion describing intense fear or horror is replaced by the criterion of change in agitated or disorganized behavior. This standardizes the diagnosis in these specific cases, leading to more rapid diagnosis and more effective therapy.

The choice of treatment was developed in this case. Psychoeducation of the key people around the patient is crucial to the success of the therapy. These patients have difficulty establishing an adequate support network. The people around the patient should be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of PTSD [14]. They can also help create an environment conducive to symptom control and avoidance of situations or people that trigger feelings of fear or other pathological behaviours [12].

Many caregivers tend to believe that psychological treatments such as cognitive-behavioural therapy play no role in cases of dual diagnosis. On the contrary, studies show a very positive response to this type of therapy [14]. Obviously, techniques must be adapted to each patient’s level of understanding and ability to communicate. The patient’s pharmacological treatment already includes an SSRI. This is one approach to treating generalized anxiety disorder. Since the patient still shows signs of anxiety, but no symptoms of current major depression, we choose to maintain this therapy at the same dose. SSRIs are safe medications and their benefits have been well studied [15].

In addition, current psychopharmacological therapy includes Risperidone. This may help reduce nightmares and flashbacks. This is why, in order to properly treat symptoms that seem to be related to post-traumatic stress disorder, a titration or doseescalation trial is being carried out [16]. Risperidone, a thirdgeneration antipsychotic, helps cognition by acting on the frontal lobe. The “conscious mind” is stimulated, and we see a reduction in nightmares and an increase in the ability to manage more complex emotions [8]. This medication is often used in schizophrenia, but can also reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety and obsessive thoughts. However, it is essential to monitor for possible side effects, especially extra-pyramidal ones.

A new possible diagnosis is post-traumatic stress disorder. And it’s in our interest to help the patient reduce her nightmares and flashbacks even further, since they affect her daily life. According to Yeh et al. [17] topiramate is effective in the treatment of post-traumatic stress. It helped reduce nightmares in 79% of patients in their study, and 86% saw a reduction in flashbacks. The reduction in nightmares will also enable deeper sleep, which will have a positive effect on generalized anxiety disorder. Topiramate can also help with weight loss [18], another important benefit in this case. It’s a well-tolerated drug with no significant side effects, and acts quickly, which would help in this case since the patient would report that her symptoms were worsening if this were the case.

9.1 Psychological Treatment

Psychotherapy plays a central role in the long-term treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with intellectual disabilities. While these patients respond well to a number of approaches, the most important limiting factor remains the degree of impairment.

Several approaches are effective in reducing symptoms: cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, Imagery Reversal Therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and psychodynamic psychotherapy. Of course, these are undertaken once pharmacological treatment has been optimized. Adaptations are important, depending on the degree of understanding and functioning of each patient studied [19]. In addition, CBT has been shown to reduce auditory hallucinations in this population. [20] Therefore, it would be appropriate to suggest CBT here. She can easily communicate verbally and has judgment and self-criticism present, albeit limited. She could benefit from therapy adapted to her functional level, which is relatively good. In addition to reducing her nightmares and auditory hallucinations, we also aimed to reduce the variety of symptoms possibly related to post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly anxiety.

9.2 Psychosocial treatment, psycho-education and other programs in the community

The social environment is very important in post-traumatic stress disorder therapy, even more so when the patient has an intellectual disability [21].

In the specific case of our patient, it is important to ensure regular visits to ensure compliance with medication. As the patient is completely dependent on her mother, it is also important to ensure that her mother also follows her treatment, since as mentioned above, she is also being treated for schizophrenia.

In general, for patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, it is important to avoid situations or elements that trigger distressing memories. The greater the patient’s intellectual impairment, the more dependent he or she will be on the environment, and the more difficult it will be for the patient to make an effort to avoid stress [20].

Educating family and friends is also very important. Raising awareness of possible crises, the possibility of triggers, the creation of a stable environment and routine, in addition to compliance with pharmacological treatment, is crucial to the success of long-term management [22]. In this case, it will be more difficult, as his mother suffers from schizophrenia.

Congenital heart disease, including that associated with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), can potentially contribute to the development of mental impairment in sufferers, although this is not systematic. Surgical and medical treatments can often improve heart health and general functioning, but they do not guarantee the prevention or resolution of neurodevelopmental problems [23].

The impact of congenital heart disease on cognitive and mental development depends on several factors, including the severity of the heart disease, the timing and effectiveness of treatment, appropriate follow-up care and individual characteristics. Some people with congenital heart disease, including those mentioned (such as tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great vessels and heart valve abnormalities), may present with mental impairments, whether or not they have undergone surgery.

Congenital heart disease can affect blood flow and, consequently, oxygen supply to the brain, with potential consequences for neurological development. Critical periods of brain development are often during pregnancy and the first years of life, and insults or disruptions at these times can have lasting effects.

It is important to stress that each individual with FASD is unique, and the effects of congenital heart disease on mental development can vary considerably. Some individuals may present only mild or moderate problems, while others may show more significant impairments [24].

Regular medical follow-up, specialized assessments, educational interventions and tailored care are essential to support individuals with FASD and congenital heart disease, particularly with regard to their cognitive and mental development needs. A multidisciplinary care plan, developed in collaboration with healthcare professionals specializing in FASD and congenital heart disease, can help optimize the well-being and development of each individual concerned [25].

In terms of prognosis, it has been shown that a combination of pharmacology and psychotherapy can have a significant impact on reducing symptoms, such as nightmares [26] and agitation with exposure and avoidance [27].

In the case of our patient, who was able to communicate easily verbally, being aware of the traumas she had experienced and being able to describe them with conviction and without collateral help explains the good prognosis. A good prognosis is also evoked if a complete follow- up is started and if psychotherapy added to pharmacological treatment is subsequently adjusted.

Conclusion

The point of this case study is to show that a dual diagnosis can be difficult to make in people with mental disabilities. The importance of diagnosing post-traumatic stress disorder in individuals with intellectual disabilities has been demonstrated. Little research has been undertaken in this area. Nevertheless, better diagnostic tools need to be developed to better meet the needs of these individuals, who may be susceptible to physical or sexual abuse resulting in psychological and emotional trauma, without being expected to speak out, because their mental impairment limits their verbal expression [28].

Caregivers should not associate any behavioral changes in these patients with their intellectual disability, but always keep in mind the possibility of an additional mental health problem.

In the case of simple trauma, i.e. a single traumatic episode such as this patient’s non-repetitive rape, the prognosis was good when EMDR, CBT and pharmacotherapy were combined over a period of 3 to 6 months, with the number of sessions varying between 10 and 20. In cases of dual diagnosis with complex trauma, the prognosis is often guarded or even poor, even in victims without intellectual deficits. This is a medico-legal problem with far-reaching consequences [29-31], which calls for consistent biopsychosocial management in the fields of care, prevention and restorative justice, if we are to have any hope of a successful recovery for these victims.

References

1. Fletcher, R.J., Barnhill, J., McCarthy, J. (2016). Diagnostic Manual-Intellectual Disability A Textbook of Diagnosis of Mental Disorders in Persons with Intellectual Disability. NADD Press.

2. Cooper, S.A., Smiley, E., Morrison, J., Williamson, A., Allan, L. (2007). Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence and associated factors. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(1), 27-35.

3. Xenitidis, K., Gratsa, A., Bouras, N., Hammond, R., Ditchfield, H., Holt, G., ... & Brooks, D. (2004). Psychiatric inpatient care for adults with intellectual disabilities: generic or specialist units? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48(1)11-18.

4. Hassiotis, A., Barron, P., O’Hara, J. (2000). Mental health services for people with learning disabilities: a complete overhaul is needed with strong links to mainstream services. BMJ, 321(7261), 583-584.

5. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

6. Cardno, A.G., & Gottesman, I.I. (2000). Twin studies of schizophrenia: From bow-and- arrow concordances to star wars Mx and functional genomics. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 97(1), 12-17.

7. Weiss,D.S., Marmar, C.R. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In J.P. Wilson, & M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner’s Handbook. (pp. 399-411). New York: Guilford Press.

8. Aurora, R.N., Zak, R.S., Auerbach, S.H,, Casey, K.R., Chowdhuri, S., et al.(2010). Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. J Clin Sleep Med, 6(4), 389-401.

9. Zigmond, A.S., & Snaith, R.P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica, 67(6), 361-370.

10. Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., & Brown, G.K. (1996). Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, 78(2), 490-498.

11. DM-ID 2 Network (2018). Integrated provincialautism and mental health services for dually diagnosed. Ontario Shores Centre for Mental Health Sciences, Whitby, Ontario.

12. Lunsky, Y., & Balogh, R. (2014). Dual diagnosis: A national study of psychiatric hospitalization patterns of people with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(3), 269-278.

13. Hassiotis, A., Strydom, A., Crawford, M., Hall, I., Omar, R., et al. (2013). Clinical and cost effectiveness of staff training in Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) for treating challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC psychiatry, 13(1), 1-13.

14. .Morrison, A.P., Frame, L., & Larkin, W. (2003). Relationships between trauma and psychosis: A review and integration. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(4), 331- 353.

15. Dagnan, D., Jahoda, A., & Kilbane, A. (2018). Developing a group for men with intellectual disabilities who have attended sex offender treatment groups: A pilot study. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 46(3), 207-214.

16. Baldwin, D.S., Anderson, I.M., Nutt, D.J., Allgulander, C., Bandelow, B., den Boer, J.A., et al. (2014). Evidencebased pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(5), 403-439.

17. Nussbaum, N.L., Anand, L., Christensen, B.K., & Nelson, L.A. (2015). Preliminary experience with Paliperidone palmitate for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a clinical chart review. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(3), 213-218.

18. Yeh, M.S., Mari, J.J., Costa, M.C., Andreoli, S.B., Bressan, R.A., et al. (2015). A double-blind randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of topiramate in a civilian sample of PTSD. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 21(5), 383-388.

19. Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Gadde KM, et al. (2007) A randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled, multicenter study to assess the efficacy and safety of topiramate controlled release in the treatment of obese type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Obes (Lond), 31(1), 140-149.

20. Mevissen, L., & de Jongh, A. (2010) PTSD and its treatment in people with intellectual disabilities. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 308-316. 21. Favrod, J., Linder, S., Pernier, S., & Chafloque, M.N. (2007) Cognitive and behavioural therapy of voices for with patients intellectual disability: Two case reports. Annals of general psychiatry 6:22.

22. Ryan, R. (2000). Post-traumatic stress disorder in persons with developmental disabilities. In A. Poindexter (ed.), Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in persons with mental retardation: Revised and updated for 2000. New York: Kingston.

23. Stenfert, K, et al. (2006). Treating chronic nightmares of sexual assault survivors with an intellectual disability - Two descriptive case studies. J Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 75-80.

24. McCarthy, J. (2001). Post-traumatic stress disorder in people with learning disability. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, 163-169.

25. Reller, M.D., Strickland, M.J., Riehle-Colarusso, T., Mahle, W.T., & Correa, A. (2008). Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. The Journal of Pediatrics, 153(6), 807-813.

26. Streissguth, A.P., Bookstein, F.L., Barr, H.M., Sampson, P.D., O’Malley, K., et al. (2004). Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(4), 228-238.

27. Astley, S.J., & Clarren, S.K. (2000). Diagnosing the full spectrum of fetal alcohol- exposed individuals: Introducing the 4-digit diagnostic code. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 35(4), 400-410.

28. Mitchell, A., et al (2006). Exploring the meaning of trauma with adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 19 131-142.

29. Tomasulo, D., et al. (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder, In R. Fletcher, E. Loschen, C. Stavrakaki, & M. First (Eds.), Diagnostic Manual-Intellectual Disability (DM-ID): A textbook of diagnosing of mental disorders in persons with intellecctual disability (pp. 365-378).

30. Kingston, N.Y, NADD Press.Sobsey, D., & Doe, T. (1991). Patterns of sexual abuse and assault. Sexuality and Disability, 9(3), 243-259.

31. Morris, S. (2003). Dual Diagnosis. Reprinted by permission of the psychiatric patient advocate office from Mental Health and Patients’ Rights in Ontario: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.