Research Article - (2023) Volume 8, Issue 10

Obstacles with Ethics in Resuscitation with Several Comorbidities

2Department of Surgical, Alahrar Tteaching Hospital, Zagazig city, Sharkia, Egypt

Received Date: Sep 26, 2023 / Accepted Date: Oct 20, 2023 / Published Date: Oct 31, 2023

Abstract

Georg von Békésy (1899-1972), as a Hungarian citizen, was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his experiments in Hungary (1923-1946) “for his discoveries of the physical mechanisms of stimulation within the cochlea”. The most significant element of Békésy’s oeuvre is the observation and description of the mechanical processes in the inner ear and the creation of a new theory on the nature of hearing. He was the first to produce a model that truly resembles the inner ear. His success is due to detailed studies on the constituents of the cochlea and a large number of measurements. It is also very important to identify how the mechanism of neural inhibition in the ear contributes to the distinction of “signal” from “noise”. For Békésy, the biophysical approach was decisive, and he connected the three sense organs (ear, skin, eye) with each other. In his oeuvre, he also combined his research in physics, communications and medicine, as well as his scientific work with art.

Keywords

Ethnicity, Comorbidity, Prognostication

Objective

A rapidly developing field of resuscitation science offers older patients with several comorbidities more efficient treatments. Patients now receive priority in emergency care at the same time. The goal of this study is to describe the problems that arise when trying to apply basic bioethical ideas to resuscitation and care after resuscitation, suggest ways to fix these problems and stress the importance of ethics that are based on evidence and agreement on how to interpret ethical principles.

Techniques

Once the article’s outline was agreed upon, subgroups of two to three authors presented narrative evaluations on ethical problems related to justice, autonomy and honesty, beneficence/ nonmaleficence and dignity, and particular practices or situations such as family presence during resuscitation and emergency research. Also, suggestions for dealing with moral dilemmas were made.

Results

Patient autonomy can be achieved through advance directives, care planning, collaborative decision-making, and truthful information sharing. To ensure this, it is necessary to train healthcare personnel, implement appropriate regulations, and provide sufficient funding. Resuscitation should aim to assist patients without endangering them, and decisions should be based on neurological prognosis and patient or family input. It is essential to avoid aggressive interventions against patient requests to preserve dignity. Factors such as age, ethnicity, comorbidity, race, income status, and geography can impact resuscitation outcomes, which raises concerns about fairness. It is recommended that families be present during resuscitation, based on available data. Autonomy in emergency research should be respected without hindering scientific progress, and efforts should be made to expand funding and increase research transparency.

Conclusion

Complex and resource-demanding procedures are necessary to solve significant ethical challenges in resuscitation science. Such initiatives need to be backed by current and upcoming research.

Background

For physicians, various ethical dilemmas are brought about by ongoing changes in medicine and the social environment in which it is performed. Rapid developments in critical care and resuscitation science have increased the possibilities for patient treatment [1,2]. Still, the aging population and the rise in the number of people with numerous comorbidities have raised questions about the efficacy of these treatments. At the same time, patient-centered care has replaced paternalistic care with a greater emphasis on the rights and values of the individual and a better-informed populace. There is a substantial body of literature on the application of vital ethical principles in resuscitation medicine [1,3-15]; see also the electronic supplementary material (ESM). Important ethical documents and guidelines have reflected and contributed to this change [2-5].

To guarantee high-quality care, evidence-based emergency care standards and associated ethical issues should develop concurrently [1,5]. However, for various reasons, different nations and cultures may understand ethical principles differently regarding resuscitation and end-of-life decisions [1,5,16,17].

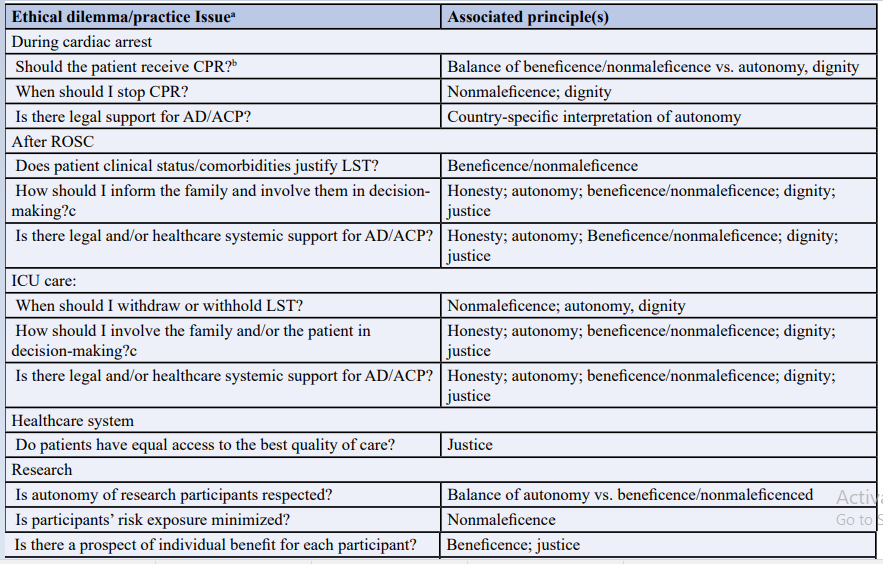

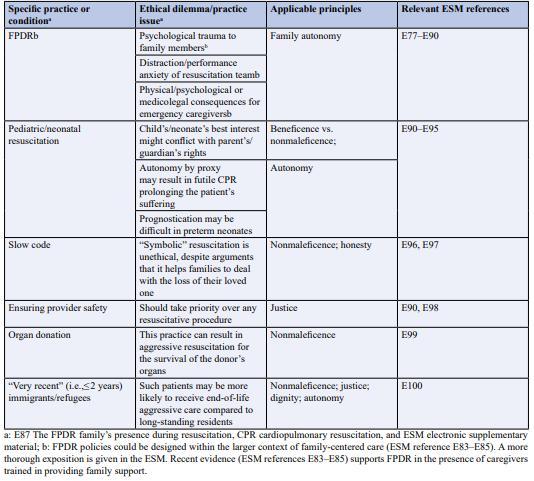

These are the goals of this narrative review: (1) to discuss current and new problems that arise when applying ethical principles to resuscitation and the critical care that follows; a brief, pertinent summary is presented in Table 1; (2) to suggest possible ways to solve these problems through actions, projects, and approaches; and (3) to stress how important it is to study evidence-based ethics and the global agreement [17] on ethical principles in resuscitation.

Patient consent for CPR is assumed unless prior knowledge of or instant access to recorded patient wishes opposing CPR is known (see also text and Table 2); recorded patient preferences are typically linked to an AD or ACP, as further examined in the respective article subsections.

As the text explains, this should involve a collaborative decision-making process. When evaluating novel and possibly helpful interventions or even standard procedures (such as using adrenaline during CPR), clinical research may be conducted to see whether there is a risk-benefit link. The following is our definition of the pertinent ethical principles: Autonomy: honoring the right to self-governance [1,7].

Sincerity: providing the patient or family with accurate and frank information on the best available research findings and clinical judgment, including any uncertainties.

Beneficence is choosing the patient’s beneficial interventions after determining the risk-benefit ratio [1,3].

To achieve a desirable end, non-maleficence refers to avoiding harm or causing the most minor damage possible [1].

Respecting the individual’s self, sustaining relationships and a sense of belonging, “being human,” and “having control” are all parts of dignity [1,18]. Regarding resuscitation and postresuscitation care, fulfillment involves avoiding disproportionate interventions and an “end-of-life” that goes against the patient’s wishes.

Justice is the equitable and just distribution of expenses, risks, and rewards. It also refers to the equality of rights to healthcare and the legal duty of healthcare professionals to provide appropriate care and distribute benefits and responsibilities relatively [1].

Table 1: Lists shared significant ethical issues with resuscitation along with related bioethical concepts

When reading the introduction, you will find definitions of ethical concepts. This text examines the relationships between ethical principles and clinical dilemmas and practice concerns. QoL, or quality of life; AD, Advance Directive; ACP, Advance Care Planning; LST, life-sustaining therapy; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DNACPR, Do Not Attempt CPR; Table 4 presents challenges related to other contexts or clinical procedures. According to the respective article subsections, recorded patient preferences are typically associated with an AD or ACP. Therefore, consent for CPR is presumed unless there is immediate access to or prior knowledge of recorded patient requests against CPR (see also text and Table 2). The essay provides additional analysis on the need for a shared decisionmaking process. Clinical research may also assess the potential benefits of typical activities (like using adrenaline during CPR) with an unknown risk-benefit relationship.

Respecting Patient’s Wishes

Protecting the autonomy of individuals experiencing cardiac arrest who are incapacitated can be achieved through advance directives, advance care planning (ACP), and talking to their loved ones to confirm their pre-existing desires. ACP and advance directives often address a person’s wishes for other lifesustaining procedures (LSTs) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) [19].

Prior Instructions

Advance directives pertain to patients who are unable to make decisions for themselves. They consist of living wills, also known as instruction and proxy directives, which designate a “healthcare proxy” with a durable power of attorney to make healthcare decisions [1,10,19,20]. A patient’s values, objectives, and preferences regarding medical issues and interventions might be summarized in a general instruction directive or described in more detail in a specific instruction directive [1,11,19,20]. Preferences like “don’t try CPR” (DNACPR) may exist.

Those in good health who form living wills could try to include a wide range of illnesses without having the necessary “medical knowledge and a grasp of the resulting conditions” [21]. This could lead to ambiguity in the directive, making it harder to apply and requiring interpretation in specific clinical situations [20]. The legal standing of advance directives varies greatly among European nations, ranging from “not mentioned in law” to “legally binding” [6, 20]. This status depends on cultural, religious, sociolinguistic, political, and medical-ethical considerations [22].

Living wills created when a person is still well may not mirror evolving preferences due to age, the onset of a significant disease, and cognitive deterioration [23,24-25]. These circumstances may also influence a doctor’s desire for medical treatment [25]. More than 70% of senior inpatients who had previously expressed their preferences regarding resuscitation may ultimately prefer that their family and doctor decide for them [26]. On the other hand, current research indicates that advance directives could encourage comfortable care and avoid excessive treatment towards the end of life [27]; this aligns with the principles of nonmaleficence and dignity.

ACP

Significant distinctions exist between ACP and advance directives. The goal of ACP is for patients and clinicians to make decisions together. It is a dynamic, iterative process that involves asking patients about their informed preferences for end-of-life care, documenting those preferences, and setting priorities and pre-specifying future treatment objectives in response. Patients, qualified healthcare providers, families, and other loved ones communicate with one another to accomplish this [28]. ACP may lessen the patient’s ethical burden upon dying, improve communication with family members, and assist the patient in adjusting to death [29].

New research on complicated and resource-intensive interventions (see ESM) suggests that ACP may lower the overall rate of “aggressive” LSTs [28], which is in line with the principles of not harming and respecting others. It also encourages congruency of care with patients’ wishes and related patient and family satisfaction. Finally, it lessens family stress, anxiety, and depression. Multiple tools, like the Physicians Orders for LSTs (POLST) forms and registry [30], along with a healthcare policy that makes it easy for emergency caregivers to access recorded patients’ goals and preferences, are required to effectively connect patients’ wishes to care plans that can be carried out.

It has been suggested that DNACPR preferences should be combined with ACP, which includes patient preferences on outcomes and other treatments (besides resuscitation), to help solve the main issues that come up with “isolated” DNACPR orders [8]. These issues include the patient or family not participating in decision-making [8], performing CPR incorrectly [3,4,6,8], performing CPR that lowers the patient’s perceived quality of life [1], and refusing to administer additional recommended therapies like painkillers and fluids [8]. The misreading of DNACPR is linked to the withholding of necessary treatment, which is not ethically justified [32].

Assent to Joint Decision-Making and Interventions

“An intervention in the health field may only be carried out after the person concerned has given free and informed consent to it,” according to Article 5 of the Biomedicine Convention [33]. The validity of consent may be influenced by three factors: (1) the availability of sufficient time for decision-making [14], (2) the presence of concurrent emotional stress [15], and (3) an individual’s capacity to comprehend crucial information about their illness and recommended treatment, evaluate the severity of their condition, weigh risks and benefits, and articulate a reasoned choice [10]. A “treat first, discuss later” strategy is required in emergencies like cardiac arrest where there are no readily available, recorded patient preferences for CPR or DNACPR orders while the patient is in cardiac arrest (Tables 1, 2).

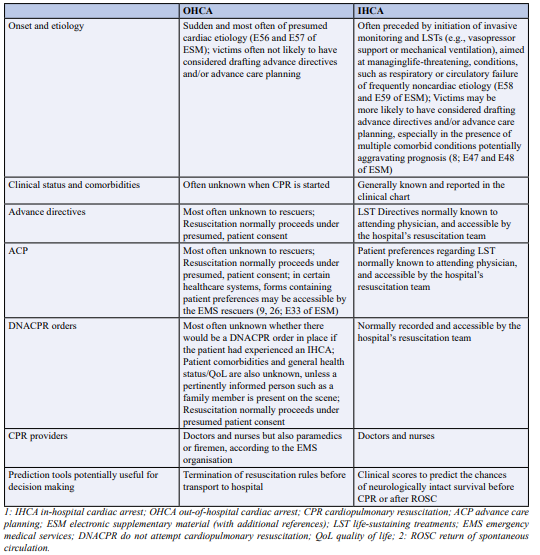

Table 2: Features of OHCA and IHCA that may have an impact on Autonomy, Beneficence/Nonmaleficence, and Autonomy

Assent to Joint Decision-Making and Interventions

An intervention in the health field may only be carried out after the person concerned has given free and informed consent to it,” according to Article 5 of the Biomedicine Convention [33]. The validity of a license may be influenced by three factors: (1) the availability of sufficient time for decision-making [14], (2) the presence of concurrent emotional stress [15], and (3) an individual’s capacity to comprehend crucial information about their illness and recommended treatment, evaluate the severity of their condition, weigh risks and benefits, and articulate a reasoned choice [10]. A “treat first, discuss later” strategy is required in emergencies like cardiac arrest where there are no readily available, recorded patient preferences for CPR or DNACPR orders while the patient is in cardiac arrest (Tables 1, 2).

To comply with strict standards for respecting patient autonomy, doctors may feel conflicted about giving patients the “full picture”-including information about scarce resources-or shielding them from stress and complex decision-making when they are already ill. Occasionally, doctors may use a “therapeutic privilege” and withhold some information [44] regarding a resuscitation decision.

Gaining Without Causing Harm

Given the potential for harm associated with medical procedures, doctors should be sure that the benefit outweighs the risk. The uncertainty around the possible advantages and disadvantages of a particular circumstance raises an ethical problem. This is more prevalent in cases where patients cannot speak, and their opinions regarding the possible advantages and disadvantages of treatments are unclear. These morally challenging choices arise in the context of CPR when deciding when to start, when to stop, and how much to use in LSTs when spontaneous circulation returns (ROSC).

There is a chance that doing CPR could hurt you. According to data gathered from 27 European countries, 75% of patients who undergo resuscitation after an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) do not achieve ROSC before hospital admission (individual, country-reported range: 50-90%), and the overall inhospital/30-day mortality rate is 90% (country-reported range: 69-99%) [45]. Comparable death statistics have been published for Australia (the year 2015, in-hospital/30-day mortality, 88%; region-specific range, 83-91%) [47], Canada (the year 2010, inhospital mortality, 90%; region-specific range, 81-94%), and the United States (the year 2010). Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury (HIBI) often leads to long-term cerebral impairment, including a permanent vegetative state, in OHCA survivors beyond hospital discharge [48]. The projected percentage of moderate-to-severe neurological impairment or mortality at 12 months post-arrest among Australian patients aged 65 years or older was 44% [49]. To avoid detrimental resuscitation efforts, it is critical to predict when CPR is unlikely to result in neurologically meaningful survival and to be aware of the patient’s values and preferences beforehand. This is challenging, particularly in OHCA, because less information is available regarding the patient’s health status and personal preferences and more uncertainty.

Therefore, in all out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCAs), CPR should be started immediately unless there are clear indications of irreversible death, a valid advance directive, or a DNACPR order (Tables 2-5). The moral default is to protect life and postpone deciding what is in the group’s best interests until pertinent data is gathered.

In contrast, most occurrences of in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) are observed and monitored, and medical staff can provide life support right away. DNACPR orders may be in place for individuals for whom CPR attempts are likely unsuccessful (Table 2; refer to ESM). A recent survey found that 22 of 32 European countries (69%) implemented DNACPR orders [5]. The pre-arrest state of patients, acute and chronic comorbidities, pre-arrest therapeutic measures, cause of cardiac arrest before arrest, and prognosis differ between IHCA and OHCA (Table 2). Risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality in the United States was 78% in 2009; among survivors, the percentages of clinically significant and severe disability were 28% and 10%, respectively [50]. A hospital’s risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality can range from 68% to 100% [51].

The initial evaluation of relevant benefits and harms should be reassessed if the first attempts at resuscitation are unsuccessful. When a patient has been in asystole for more than 20 minutes while receiving advanced life support, the European Resuscitation Council’s (ERC) ethical standards advise healthcare professionals to consider stopping resuscitation efforts in the absence of a reversible reason [3]. When OHCA lasts more than 30 minutes, survival with a favorable neurological prognosis is often unlikely [3]. But as we’ll see, there are exceptions to this norm (see ESM), and the development of extracorporeal CPR has put it under scrutiny recently [52]. Clinical decision aids have been proposed (34; see above and ESM) about IHCA; however, there is still a need for a comprehensive external validation of the corresponding clinical scoring system.

Evaluating HIBI severity can guide the morally tricky decision of whether and when to forgo providing these patients with disproportionate care. In 2014, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and the ERC jointly released recommendations for neurological prognostication following cardiac arrest [53]. These guidelines are based on a multimodal approach that combines relevant studies and clinical examination to accurately predict a poor neurological outcome in comatose patients who do not have a motor response to pain or have an extensor answer. This must happen at least three days after ROSC. Nevertheless, the evidence supporting these predictors is of low quality, and prolonged LST may be recommended when the prognosis seems unclear or the indicators produce inconsistent results.

The inconsistent definitions of a poor neurological outcome [54] constitute another drawback for neurological prognostication indices. The quality of life (QoL) reported by cardiac arrest survivors or their caregivers is typically lower than what conventional outcome measures indicate [55]. In evaluating the suitability of resuscitation measures, prognostication tools ought to be predicated on results reported by patients and families, as opposed to those written by clinicians. Studies on cardiac arrest should evaluate patient- or family-reported outcomes and use QoL indicators [56,57].

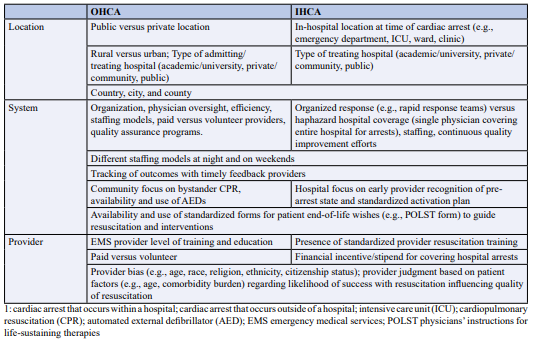

Table 3: Justice-related issues in cardiac arrest, separated by OHCA versus IHCA

Certain hospital services, such as extracorporeal CPR, postROSC cardiac catheterization, and targeted temperature control, are expensive, labor-intensive, and require specialist personnel whose availability varies considerably. This resource is logically concentrated in urban tertiary institutions with access to modern cardiovascular treatment, even in high-resource nations where extracorporeal CPR is widely used (see ESM). Even less often, and usually limited to Emergency Medical Services systems operated by doctors with mobile intensive care unit capability, is the use of extracorporeal CPR outside of hospitals [64].

The justice of resuscitation might be enhanced by focusing on better and more consistent provider training, bystander CPR, automated external defibrillator use and availability, and more standardized resuscitation techniques. System-level factor modifications probably need a central champion, committed money, and organizations that are flexible and open to change. Research suggests that if systemic factors, feedback, CPR quality, outcome monitoring, and training are given more attention, cardiac arrest survival rates may rise over time [46].

Rationing in resuscitation raises questions about the impartiality and moral rectitude of the standards used to make DNACPR/LST judgments [65]. Based on futility and variations in prognosis and LST cost, limited resources may be allocated utilitarianly [65,66]. According to one definition, futility is “the application of significant resources without a convincing expectation that the patient will recover to a level of relative independence or be interactive with their surroundings” [65]. Weak people, such as the elderly, people with disabilities, or those with long-term, inherited, or genetic diseases or abnormalities, may be unfairly or unethically denied helpful treatment if the words “considerable,” “reasonable,” “relative independence,” and “interactive” are not defined [65].

12. Particular Therapeutic Procedures or Situations

These include end-of-life care for “very recent” (i.e., ≤ 2 years) immigrants or refugees, slow coding, family present during resuscitation, provider safety, and organ donation. Table 4 summarizes ethical challenges, which are covered in full in the ESM.

Table 4: Ethical Difficulties Concerning Particular Clinical Procedures or Situations

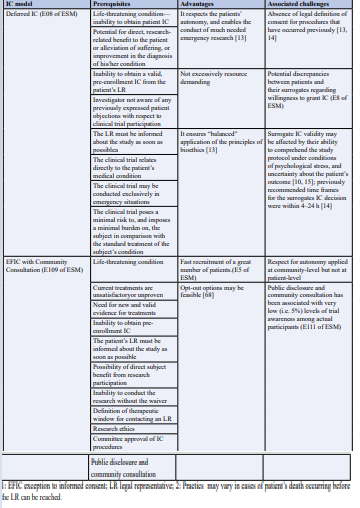

Concerns about Ethics in Emergency Research

Respecting autonomy in cardiac arrest research is challenging since pre-enrollment informed consent cannot be obtained because of the urgent need for resuscitation [13,14]. Deferred consent and informed consent (EFIC) exceptions with prior community involvement [13,67] are other ways to obtain consent for low-risk research that are morally and publicly acceptable [13]. In deferred support, informed consent is requested for continued participation after the patient, next-of-kin, or legally authorized representative is notified about the study as soon as possible. This consent model can be used in emergency research involving patients incapacitated in the European Union [13]. The protocols may change depending on how much transparency and informing the family balance against the burden or harm that comes with it if the patient passes away before the next-of-kin can be contacted. The consent model known as EFIC allows community members to request “no study” to opt out of receiving information shared with the relevant populations [68]. This consent model can be applied to emergency research conducted in the United States (13; ESM). Table 5 lists the features of these consent models together with the moral dilemmas they raise [1,13-15]. One such dilemma is the legitimacy of consent. Other types of support, including prospective and integrated support, have been described elsewhere [1]. Withdrawing permission after enrollment in a trial can create bias since participants who do worse are likelier to do so [69]. Certain agencies (like the US Food and Drug Administration) prohibit participants from removing data already gathered until they revoke their consent. Still, not all authorities (like the European Union authorities) do. Further difficulties are explained in depth in the ESM.

Table 5: Lists the attributes of consent models substituted for informed consent (IC) obtained before enrollment

Profit-making and non-profit academic research have been asked to be more open about trials that have not been reported. This call for transparency addresses flawed study design, selective reporting, ghostwriting, and authorship. Journals now require writers to disclose the involvement of sponsors and their contributions in various aspects of the research process to ensure transparency. Another critical concern in research is prioritizing research related to public health needs. The number of randomized clinical trials for cardiac arrest resuscitation is significantly lower than guidelines for conditions like heart failure and stroke despite the high mortality burden associated with cardiac arrest. The funding for expensive, patent-protected drugs and devices has been disproportionately higher than for much-needed, non-commercial academic resuscitation research on affordable, commonly used medications with uncertain effectiveness. Overcoming cultural, religious, legal, and socioeconomic barriers is necessary to implement harmonized policies that support resource-intensive techniques and protect patient autonomy [32,33].

Examples from states like Oregon, USA [31,32] indicate that the public should be informed in an “unbiased manner” about the advantages and drawbacks of resuscitation, as well as the individual prognosis of illness. This information should ideally be organized and provided “free of charge” to patients and their families. It may also assist patients and their families in expressing their preferences. Patients and their families must be cognizant of their rights derived from fundamental ethical principles, as well as the scope of these rights. Such programs and actions could help vulnerable populations (such as those with low socioeconomic status and recent immigrants or refugees) and society at large.

To incorporate respect for autonomy and other ethical principles into their everyday practice, caregivers who are now in active roles should undergo ethical practice training and then a predetermined skill-level certification. This would probably encourage doctors and nurses to understand essential concepts more consistently, and it would also make it easier to implement the structured, shared decision-making processes that are currently advised [9,10] in a way that is ideally standardized. Furthermore, pre-graduate instruction in medical ethics would provide the next generation of doctors and healthcare workers with sufficient theoretical understanding of the fundamental concepts and how to apply them, along with clear definitions. This should be followed by training in ethical practice and relevant certification.

Harmonizing the nomenclature in ethical practices will enhance communication and avoid stakeholder misunderstandings. For example, agreement should be obtained on the best abbreviation for not performing resuscitative interventions, such as DNR (do not resuscitate), DNAR (do not attempt resuscitation), or DNACPR. Furthermore, it would be good to characterize any conceptual distinctions between withdrawing and withholding life-sustaining treatment (LST) in a way that is as inclusive as possible. While LST withholding refers to “passively allowing the patient to die,” some ethicists view LST withdrawal as actively causing death [72]. However, given that the outcome of these activities is essentially the same, consequentialists do not find any ethically significant distinction [72]. Current European standards for indications and treatment intensity for palliative sedo-analgesia are quite precise One of the biggest challenges facing both rich and emerging nations is dealing with the problem of scarce resources. Universal access to the most excellent emergency care available, including costly technological innovations like extracorporeal CPR [64], appears to be a theoretical rather than a feasible goal that will be attained shortly [5]. On the other hand, structured international resuscitation education, ideally backed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and international resuscitation councils, might significantly increase the widespread use of easy and beneficial interventions like bystander CPR. The World Health Organization (WHO) has already released guidelines and initiated programs to support the basic resuscitation of newborns in developing nations. This will increase the accessibility of emergency care and may lower the morbidity, disability, and death in this susceptible population segment.

In terms of research, data-sharing rules might be used to encourage transparency [73], and government funding for resuscitation research could be increased to align it more with the burden of cardiac arrest mortality [71]. Furthermore, balancing commercial interests with investigators’ goals of promoting science should strengthen the ethical credibility of relationships between the public and private sectors [74]. Finally, families and patients may actively participate in the creation of clinical and ethical practice guidelines as well as research objectives.

In summary, there are significant ethical issues with the quickly developing field of resuscitation research that require extensive, well-coordinated, and occasionally resource-intensive interventions to resolve. Research is needed now and in the future to support the effects of such actions on society, ethics, and the physical world.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

HAS, ME: contributed to the conception and design of

Mr. AKE organised the database and performed the statistical analysis.

HAS,KS: wrote sections of the manuscript and prepared tables.

MIF, AB,MR: contributed to the manuscript. revision. All authors read, approved, and equally shared the submitted version.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author’s request.

Funding Sources

None.

Ethics Declarations

Declaration and ethical consent

Ethical clearance was obtained from Zagagic University, Faculty of Medicine, Institutional Health Research Ethics (IHRERC), and written informed consent was obtained from the Review IHRERC under No. (ethical protocol number ZUIRB#9990888-2023). Written informed consent was obtained from the Zagazig University Hospital database in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Mentzelopoulos, S. D., Haywood, K., Cariou, A., Mantzanas, M., & Bossaert, L. (2016). Evolution of medical ethics in resuscitation and end of life. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care, 10, 7-14. 2. Parsa-Parsi, R.W. (2017). The revised declaration of Geneva: a modern- day physician’s pledge. JAMA, 318:1971-1972.

3. Bossaert, L. L., Perkins, G. D., Askitopoulou, H., Raffay, V. I., Greif, R., Haywood, K. L., ... & Xanthos, T. T. (2015). ethics of resuscitation and end-of-life decisions section Collaborators. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 11. The ethics of resuscitation and end-of-life decisions. Resuscitation, 95, 302-311.

4. Australian Resuscitation Council; New Zealand Resuscitation Council (2015) Section 10: guideline 10.5—legal and ethical issues related to resuscitation. Australian Resuscitation Council website. https://resus.org.au/guidelines/. Accessed 9 May 2018

5. Mentzelopoulos, S. D., Bossaert, L., Raffay, V., Askitopoulou, H., Perkins, G. D., Greif, R., Haywood, K., Van de Voorde, P., & Xanthos, T. (2016). A survey of key opinion leaders on ethical resuscitation practices in 31 European Countries. Resuscitation, 100, 11–17.

6. Mancini, M. E., Diekema, D. S., Hoadley, T. A., Kadlec, K. D., Leveille, M. H., McGowan, J. E., Munkwitz, M. M., Panchal, A. R., Sayre, M. R., & Sinz, E. H. (2015). Part 3: Ethical Issues: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 132(18 Suppl 2), S383– S396.

7. O’Neill, O. (1984). Paternalism and partial autonomy. J Med Ethics, 10, 173-178

8. Fritz, Z., Slowther, A.M., Perkins, G.D. (2017). Resuscitation policy should focus on the patient, not the decision. BMJ 356:j813.

9. Kon, A. A., Davidson, J. E., Morrison, W., Danis, M., & White, D. B. (2016). Shared Decision-Making in Intensive Care Units. Executive Summary of the American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society Policy Statement. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 193(12), 1334–1336.

10. Council of Europe (2014). Guide on the decision-making process regard-ing medical treatment in end-of-life situations. Bioethics.net website. http://www.bioethics. net/2014/05/council-of-europe-launches-guide-on-decisionmaking-process-regarding-medical-treatment-in-end-oflifesituations/. Accessed 9 May 2018

11. Nolan, J. P., Soar, J., Cariou, A., Cronberg, T., Moulaert, V. R., Deakin, C. D., ... & Sandroni, C. (2015). European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine 2015 guidelines for post-resuscitation care. Intensive care medicine, 41, 2039-2056.

12. Perkins, G. D., Jacobs, I. G., Nadkarni, V. M., Berg, R. A., Bhanji, F., Biarent, D., ... & Zideman, D. A. (2015). Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein resuscitation registry templates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International liaison Committee on resuscitation (American heart association, European resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand Council on resuscitation, heart and stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican heart Foundation, resuscitation Council of southern Africa .... Circulation, 132(13), 1286- 1300.

13. Mentzelopoulos, S. D., Mantzanas, M., van Belle, G., & Nichol, G. (2015). Evolution of European Union legislation on emergency research. Resuscitation, 91, 84-91.

14. Booth, M.G, (2007). Informed consent in emergency research: a contradic-tion in terms. Sci Eng Ethics, 13, 351-359.

15. Kompanje, E. J., Maas, A. I., Menon, D. K., & Kesecioglu, J. (2014). Medical research in emergency research in the European Union member states: tensions between theory and practice. Intensive care medicine, 40, 496-503.

16. Gibbs, A. J., Malyon, A. C., & Fritz, Z. B. M. (2016). Themes and variations: an exploratory international investigation into resuscitation decision-making. Resuscitation, 103, 75-81.

17. Sprung, C. L., Truog, R. D., Curtis, J. R., Joynt, G. M., Baras, M., Michalsen, A., ... & Avidan, A. (2014). Seeking worldwide professional consensus on the principles of endof-life care for the critically ill. The Consensus for Worldwide End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care Units (WELPICUS) study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 190(8), 855-866.

18. Enes, S. P. D. (2003). An exploration of dignity in palliative care. Palliative medicine, 17(3), 263-269.

19. Martin, D. K., Emanuel, L. L., & Singer, P. A. (2000). Planning for the end of life. The Lancet, 356(9242), 1672- 1676.

20. Andorno, R., Brauer, S., & Biller-Andorno, N. (2009). Advance health care directives: towards a coordinated European policy?. European journal of health law, 16(3), 207-227.

21. Fagerlin, A., & Schneider, C. E. (2004). Enough: the failure of the living will. Hastings Center Report, 34(2), 30-42.

22. Sulmasy, D. P. (2018). Italy’s New advance directive law: when in Rome…. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(5), 607-608.

23. Wittink, M. N., Morales, K. H., Meoni, L. A., Ford, D. E., Wang, N. Y., Klag, M. J., & Gallo, J. J. (2008). Stability of preferences for end-of-life treatment after 3 years of followup: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Archives of internal medicine, 168(19), 2125-2130.

24. Puchalski, C. M., Zhong, Z., Jacobs, M. M., Fox, E., Lynn, J., Harrold, J., ... & Teno, J. M. (2000). Patients who want their family and physician to make resuscitation decisions for them: Observations from SUPPORT and HELP. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(S1), S84-S90.

25. Silveira, M. J., Kim, S. Y., & Langa, K. M. (2010). Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(13), 1211- 1218.

26. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg, A., Rietjens, J. A., & Van der Heide, A. (2014). The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliative medicine, 28(8), 1000-1025.

27. Vandervoort, A., Houttekier, D., Van den Block, L., van der Steen, J. T., Vander Stichele, R., & Deliens, L. (2014). Advance care planning and physician orders in nursing home residents with dementia: a nationwide retrospective study among professional caregivers and relatives. Journal of pain and symptom management, 47(2), 245-256.

28. Jesus, J. E., Aberger, K., Baker, E. F., Limehouse Jr, W. F., & Moskop, J. (2017). Physicians on the Interpretation of Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Therapy (POLST).

29. Tolle, S.W., & Teno, J.M. (2017). Lessons from Oregon in embracing complexity in end-of-life care. N Engl J Med, 376, 1078-1082.

30. Fritz, Z., & Fuld, J. (2010). Ethical issues surrounding do not attempt resuscitation orders: decisions, discussions and deleterious effects. Journal of medical ethics, 36(10), 593- 597.

31. Convention for the protection of human rights and dignity of the human being with regard to the application of biology and medicine: conven-tion on human rights and biomedicine. Oviedo, 4.IV.1997.

32. Ebell, M. H., Jang, W., Shen, Y., Geocadin, R. G., & Get With the Guidelines–Resuscitation Investigators (2013). Development and validation of the Good Outcome Following Attempted Resuscitation (GO-FAR) score to predict neurologically intact survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA internal medicine, 173(20), 1872–1878.

33. Scheunemann, L. P., Arnold, R. M., & White, D. B. (2012). The facilitated values history: helping surrogates make authentic decisions for incapacitated patients with advanced illness. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 186(6), 480-486.

34. Griffith, D. M., Salisbury, L. G., Lee, R. J., Lone, N., Merriweather, J. L., & Walsh, T. S. (2018). Determinants of health-related quality of life after ICU: importance of patient demographics, previous comorbidity, and severity of illness. Critical care medicine, 46(4), 594-601.

35. Venkat, A., & Becker, J. (2014). The effect of statutory limitations on the authority of substitute decision makers on the care of patients in the intensive care unit: case examples and review of state laws affecting withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatment. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 29(2), 71-80.

36. Schenker, Y., Tiver, G. A., Hong, S. Y., & White, D. B. (2012). Association between physicians’ beliefs and the option of comfort care for critically ill patients. Intensive care medicine, 38, 1607-1615. 37. Anesi, G. L., & Halpern, S. D. (2016). Choice architecture in code status discussions with terminally ill patients and their families. Intensive care medicine, 42, 1065-1067.

38. Ernecoff, N. C., Curlin, F. A., Buddadhumaruk, P., & White, D. B. (2015). Health care professionals’ responses to religious or spiritual statements by surrogate decision makers during goals-of-care discussions. JAMA internal medicine, 175(10), 1662-1669.

39. Lipkus, I. M. (2007). Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations. Medical decision making, 27(5), 696-713.

40. Periyakoil, V. S., Neri, E., Fong, A., & Kraemer, H. (2014). Do unto others: doctors’ personal end-of-life resuscitation preferences and their attitudes toward advance directives. PloS one, 9(5), e98246.

41. Richard, C., Lajeunesse, Y., & Lussier, M. T. (2010). Therapeutic privilege: between the ethics of lying and the practice of truth. Journal of medical ethics, 36(6), 353-357.

42. Gräsner, J. T., Lefering, R., Koster, R. W., Masterson, S., Böttiger, B. W., Herlitz, J., ... & Zeng, T. (2016). EuReCa ONEâ¿¿ 27 Nations, ONE Europe, ONE Registry: A prospective one month analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in 27 countries in Europe. Resuscitation, 105, 188-195.

43. Daya, M. R., Schmicker, R. H., Zive, D. M., Rea, T. D., Nichol, G., Buick, J. E., ... & Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. (2015). Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival improving over time: results from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC). Resuscitation, 91, 108-115.

44. Beck, B., Bray, J., Cameron, P., Smith, K., Walker, T., Grantham, H., ... & Finn, J. (2018). Regional variation in the characteristics, incidence and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Australia and New Zealand: results from the Aus-ROC Epistry. Resuscitation, 126, 49-57.

45. Pichler, G., & Fazekas, F. (2016). Cardiopulmonary arrest is the most frequent cause of the unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: A prospective population-based cohort study in Austria. Resuscitation, 103, 94-98.

46. Andrew, E., Mercier, E., Nehme, Z., Bernard, S., & Smith, K. (2018). Long-term functional recovery and healthrelated quality of life of elderly out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation, 126, 118-124.

47. Girotra, S., Nallamothu, B. K., Spertus, J. A., Li, Y., Krumholz, H. M., & Chan, P. S. (2012). Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(20), 1912-1920.

48. Merchant, R. M., Berg, R. A., Yang, L., Becker, L. B., Groeneveld, P. W., Chan, P. S., & American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelinesâ?Resuscitation Investigators. (2014). Hospital variation in survival after inâ?hospital cardiac arrest. Journal of the American Heart Association, 3(1), e000400.

49. Nolan, J. P., & Sandroni, C. (2017). In this patient in refractory cardiac arrest should I continue CPR for longer than 30 min and, if so, how?. Intensive Care Medicine, 43(10), 1501- 1503.

50. Sandroni, C., Cariou, A., Cavallaro, F., Cronberg, T., Friberg, H., Hoedemaekers, C., ... & Soar, J. (2014). Prognostication in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: an advisory statement from the European Resuscitation Council and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive care medicine, 40, 1816-1831.

51. Sandroni, C., & Nolan, J. P. (2015). Neuroprognostication after cardiac arrest in Europe: new timings and standards. Resuscitation, 90, A4-A5.

52. Smith, K., Andrew, E., Lijovic, M., Nehme, Z., & Bernard, S. (2015). Quality of life and functional outcomes 12 months after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation, 131(2), 174- 181.

53. Lilja, G., Nielsen, N., Bro-Jeppesen, J., Dunford, H., Friberg, H., Hofgren, C., ... & Cronberg, T. (2018). Return to work and participation in society after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 11(1), e003566.

54. Calvert, M., Kyte, D., Mercieca-Bebber, R., Slade, A., Chan, A. W., King, M. T., ... & Groves, T. (2018). Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: the SPIRIT-PRO extension. Jama, 319(5), 483- 494.

55. Kompanje, E. J., Piers, R. D., & Benoit, D. D. (2013). Causes and consequences of disproportionate care in intensive care medicine. Current opinion in critical care, 19(6), 630-635.

56. Epker, J. L., Bakker, J., & Kompanje, E. J. (2011). The use of opioids and sedatives and time until death after withdrawing mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drugs in a Dutch intensive care unit. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 112(3), 628-634.

57. Bakker, J., Jansen, T. C., Lima, A., & Kompanje, E. J. (2008). Why opioids and sedatives may prolong life rather than hasten death after ventilator withdrawal in critically ill patients. The American journal of hospice & palliative care, 25(2), 152–154.

58. Berdowski, J., Berg, R. A., Tijssen, J. G., & Koster, R. W. (2010). Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: Systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation, 81(11), 1479–1487.

59. Nichol, G., Thomas, E., Callaway, C. W., Hedges, J., Powell, J. L., Aufderheide, T. P., Rea, T., Lowe, R., Brown, T., Dreyer, J., Davis, D., Idris, A., Stiell, I., & Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators (2008). Regional variation in outof-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA, 300(12), 1423–1431.

60. Sasson, C., Magid, D. J., Chan, P., Root, E. D., McNally, B. F., Kellermann, A. L., & Haukoos, J. S. (2012). Association of neighborhood characteristics with bystander-initiated CPR. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(17), 1607-1615.

61. Lamhaut, L., Hutin, A., Puymirat, E., Jouan, J., Raphalen, J. H., Jouffroy, R., ... & Carli, P. (2017). A Pre-Hospital Extracorporeal Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (ECPR) strategy for treatment of refractory out hospital cardiac arrest: An observational study and propensity analysis. Resuscitation, 117, 109-117.

62. Vogel, L. (2011). Can rationing possibly be rational?.

63. Arora, C., Savulescu, J., Maslen, H., Selgelid, M., & Wilkinson, D. (2016). The Intensive Care Lifeboat: a survey of lay attitudes to rationing dilemmas in neonatal intensive care. BMC Medical Ethics, 17, 1-9.

64. Callaway, C.W. (2014). Studying community consultation in exception from informed consent trials. Crit Care Med, 42, 451-453.

65. Nelson, M. J., DeIorio, N. M., Schmidt, T. A., Zive, D. M., Griffiths, D., & Newgard, C. D. (2013). Why persons choose to opt out of an exception from informed consent cardiac arrest trial. Resuscitation, 84(6), 825-830.

66. Jansen, T. C., Bakker, J., & Kompanje, E. J. (2010). Inability to obtain deferred consent due to early death in emergency research: effect on validity of clinical trial results. Intensive care medicine, 36, 1962-1965.

67. Moorthy, V. S., Karam, G., Vannice, K. S., & Kieny, M. P. (2015). Rationale for WHO’s new position calling for prompt reporting and public disclosure of interventional clinical trial results. PLoS medicine, 12(4), e1001819.

68. Ornato, J. P., Becker, L. B., Weisfeldt, M. L., & Wright, B. A. (2010). Cardiac arrest and resuscitation: an opportunity to align research prioritization and public health need. Circulation, 122(18), 1876-1879.

69. Melltorp, G., & Nilstun, T. (1997). The difference between withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment. Intensive care medicine, 23, 1264-1267.

70. Kiley, R., Peatfield, T., Hansen, J., & Reddington, F. (2017). Data sharing from clinical trials—a research funder’s perspective. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(20), 1990-1992.

71. Tierney, W. M., Meslin, E. M., & Kroenke, K. (2016). Industry support of medical research: important opportunity or treacherous pitfall?. Journal of general internal medicine, 31, 228-233.

Copyright: © 2025 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.