Case Report - (2023) Volume 8, Issue 9

Coping Strategies of Female Adult Survivors of Sexual, Physical, and Combined Abuse

Received Date: Aug 23, 2023 / Accepted Date: Sep 04, 2023 / Published Date: Sep 10, 2023

Abstract

This study explored differences in coping strategies over time that might occur among women who experienced sexual, physical, or combined sexual and physical childhood abuse. Independent variables of the study were Type of Abuse (Type: Sexual, Physical, and Combined) and the Coping Time Frame (Time: Then and Now). The dependent variables were the five coping strategies (Avoidance, Expressive, Nervous/Anxious, Cognitive, and Self-Destructive). The hypotheses of the study pertained to significant differences among three types of abuse and between Then and Now coping time frames, and interaction between the Type and Time on five coping strategies. Forty-five female survivors were administered a consent form, How I Deal with Things Scale, and a General Information Questionnaire. The results of this study showed that survivors of combined sexual and physical abuse in childhood tend to use emotion-focused coping strategies (avoidance, nervous/anxious, and self-destructive behavior) more than those who had experienced sexual or physical abuse alone. Also, all three types of abuse survivors tend to use problem-focused coping strategies (expressive and cognitive) more during their adulthood to cope with their abuse, whereas emotion-focused coping strategies (avoidance and self-destructive behaviors) are used more when the abuse first occurs.

Keywords

Child sexual abuse, Child physical abuse, Combined abuse, Joint abuse, Adverse childhood experiences, Childhood abuse and women’s health, Coping strategies by abuse victims

Introduction

Women’s and children’s protective movements have brought the problem of child abuse to the forefront of society and greatly enhanced the social and professional concerns worldwide in the 21st century. Childhood abuse has been linked to many longterm health impacts such as risky health behaviors, chronic health conditions, low life potential, and early death. The risk of these outcomes increases with the increased number of adverse childhood experiences [1]. The National Children’s Alliance (NCA) is an accrediting body for more than 850 Children’s Advocacy Centers (CACs) in all 50 states of America providing comprehensive services to victims of child abuse under the age of 18. Two of the most harmful adverse childhood experiences are sexual and physical abuse.

In 2021, CACs served 386,191 abused children nationwide (64% females, 33% males and 3% undisclosed); of these 65% were sexually abused and 20% were physically abused [2]. Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was considered an uncommon problem until the late 70’s [3,4]. However, in recent years, the Child Protective Services agencies report it to be a widespread problem, finding evidence every nine minutes for a case of CSA. Although the exact prevalence is unknown, the most current estimates about prevalence of CSA are that 1 in 5 girls and 1 in 20 boys are reported to be victimized by an adult [5].

The negative sequelae of childhood abuse have a long-term detrimental impact on mental and physical health of the victims [6,7]. Even though this has been studied and reported well in the literature [8,9], many healthcare providers do not take time or do not know how to explore these issues with their adult female patients. Often when women seek medical help for their health issues, many healthcare providers do not enquire about women’s childhood abuse, which may be an important etiological factor related to their current health issues [10-13]. Not dealing with these earlier issues may hinder the success of treatment and subsequent recovery because the cause of the problem remains unaddressed.

Understanding how women cope with the aftermath of childhood abuse is essential to creating effective and efficient interventions for promoting recovery [14,15]. The present study used Burt and Katz’s [16] conceptualization of coping with trauma as “efforts made in response to stimuli experienced as threatening or stressful-efforts aimed both at reducing the anxiety that those stimuli create and at reducing the interference of the stimuli with one’s capacity to function” (p. 345). Abuse victims use either emotion-oriented coping strategies that involve escaping the stressor by avoidance or problem-oriented coping strategies that involve changing the stressor by approach [17]. Some studies [18,19] have identified coping strategies with childhood abuse as the mediating factors amenable to intervention and having an influence on recovery. However, there is a paucity of research delineating these coping strategies and their relationship to adjustment in adulthood [20]. A comprehensive review of empirical studies reported only ten studies that identified and described coping strategies of CSA victims [14,21-29]. Several of these studies are qualitative and they reported a large number of coping strategies; some used by only a few individuals [30]. Also, they were predominantly on CSA alone; combined CSA and CPA which is more prevalent was not the focus. Thus, more quantitative research is warranted for a more consistent understanding of the coping strategies used by not only the CSA victims, but also the combined (sexual and physical) abuse victims.

The purpose of the present study was to explore differences in coping strategies over time which might occur among women who experienced sexual, physical, or combined sexual and physical childhood abuse. Independent variables of the study were Type of Abuse (Type: Sexual, Physical, and Combined) and the Coping Time Frame (Time: Then and Now). The dependent variables were the five coping strategies measured by the “How I Deal with Things Scale” (Avoidance, Expressive, Nervous/ Anxious, Cognitive, and Self-Destructive). The hypotheses of the study pertained to significant differences among three types of abuse and between Then and Now coping time frames, and interaction between the Type and Time on five coping strategies.

The physical and sexual abuse definitions by the Texas Family Code were used as the abuse criteria for the present study [31]. Both forms of abuse can be committed by either a family or nonfamily member, and the definitions apply to children younger than 18 who are not married.

Physical abuse is defined as: Physical injury that results in substantial harm to the child, or the genuine threat of substantial harm from physical injury to the child, including an injury that is at variance with the history or explanation given and excluding an accident or reasonable discipline by a parent, guardian, or managing or possessory conservator that does not expose the child to a substantial risk of harm.

Sexual abuse is defined as: Sexual contact, sexual intercourse, or sexual conduct, as those terms are defined by Section 43.01, Penal Code, sexual penetration with a foreign object, incest, sexual assault, or sodomy inflicted on, shown to, or intentionally practiced in the presence of a child if the child is present only to arouse or gratify the sexual desires of any person; (2) compelling or encouraging the child to engage in sexual conduct as defined by Section 43.01, Penal Code , including compelling or encouraging the child in a manner that constitutes an offense of trafficking of persons under Section 20A.02(a)(7) or (8), Penal Code , prostitution under Section 43.02(b), Penal Code, or compelling prostitution under Section 43.05(a)(2), Penal Code; (3) or causing, permitting, encouraging, engaging in, or allowing the photographing, filming, or depicting of the child if the person knew or should have known that the resulting photograph, film, or depiction of the child is obscene as defined by Section 43.21, Penal Code, or pornographic.

The five coping strategies developed by Burt and Katz [16] were measured by the How I Deal with Things Scale and they are Avoidance, Expressive, Nervous/Anxious, Cognitive, and SelfDestructive.

Method

2.1 Participants

Forty-five female survivors between 19 and 62 (M=39, SD=10.63) volunteered to participate in this study. All had received counseling as adults at the mental health agencies of a West Texas community and all were abused before age 18. The volunteers were sought until there were 15 women in each group who experienced childhood abuse of three different kinds: Sexual (SA), Physical (PA), and Combined Abuse (CA). They were administered a consent form, How I Deal with Things Scale, and a General Information Questionnaire.

2.2 Measures

The General Information Questionnaire included demographic information and questions concerning whether the abuse was sexual and/or physical, at what age it began, the extent and length of the abuse, relationship to the perpetrator(s), and whether any counseling took place at the time of the abuse or later.

How I Deal with Things Scale is a 33-item scale, which was developed to measure emotion-focused and problem-focused strategies of coping with sexual assault. This scale showed consistency reliabilities for the subscales ranging from .65 to .75 and test-retest reliabilities ranging from .68 to .83 with a factor analysis yielding five coping factors: avoidance, expressive, nervous/anxious, cognitive, and self-destructive [16]. Examples of scale items are: “Avoiding people, places, or situations that remind you of the abuse”-Avoidance; “Taking to family, friends, or others, about your feelings, and trying to get support from them in dealing with your feelings.”-Expressive;” Feeling irritable, cross with others, or like you are about to explode”–Nervous/Anxious; “Trying to understand what happened to you, and why you have felt the ways you have.”-Cognitive; and “Drinking alcohol, or taking illegal drugs.”-Self-destructive. Later the scale was modified to measure childhood coping strategies for child sexual abuse [32]. With the permission of the author of the scale, the modified scale was used for both physical and sexual childhood abuse. Avoidance, Nervous/Anxious, and Self-Destructive are considered more emotion-focused, while Expressive and Cognitive are seen as more problem-focused coping strategies.

The data for three main hypotheses were analyzed by a twoway mixed model 3 x 2 factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) yielding two main effects and an interaction effect on scores for the five coping strategies. All post-hoc pairwise comparisons were done by using Tukey’s HSD test. The alpha level for all tests was set at .05.

Results

The abuse was reported to have continued past 18 years of age for 53% of the women in the PA group, 13% of the women in the SA group, and 33% of the women in the CA group. Family members abused 100% of the women in the PA group (20% abused additionally by others) and 90% of the women in the SA group (27% abused additionally by others). In the CA group, it was the family members who physically abused 100% of the women (27% abused additionally by others) and sexually abused 80% of them (33% abused additionally by others). The trauma of intercourse was inflicted on 40% of the SA group, and on 60% of the CA group. All women were abused before age 18, however, the abuse began before age 11 for most of the participants (sexual-93%; physical-73%; combined-100%). Participation in 12-step groups was acknowledged by 73% of the SA Group, 67% of the PA group, and 87% of the CA group.

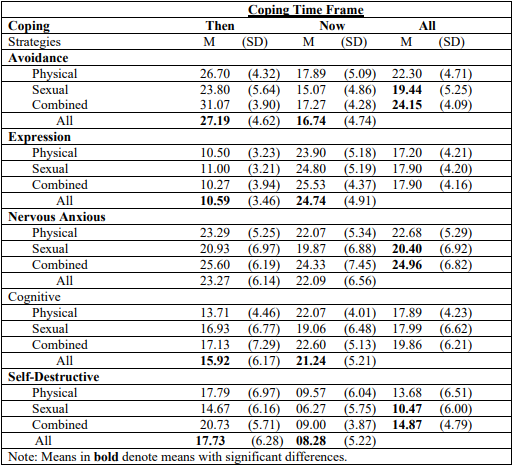

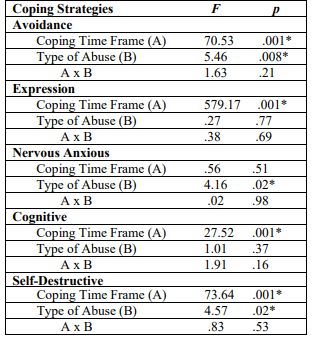

Table 1 presents the mean coping strategies scores and standard deviations for the five coping strategies. A summary of F and p values is presented in Table 2 for the mixed model factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis for five coping strategies.

Table 1: Mean Coping Strategies scores and standard deviations for Type of Abuse x Coping Times Frame.

Table 2: F and p values from the factorial analysis of variance for the Coping Strategies scores for Type of Abuse x Coping Times Frame.

The 3 x 2 mixed model factorial ANOVA results showed the following significant main effects of Type of Abuse on coping strategies scores: Avoidance (F2,42=5.46, p=.008; CA group M >SA & PA), Nervous/Anxious (F2,42=4.16, p =.02; C group M >SA & PA), and Self-Destructive (F2,42=4.57, p=.02; CA group M >SA & PA). Tukey HSD test results for the pairwise comparisons for Avoidance, Nervous/Anxious, and Self-Destructive coping strategies indicated only one pairwise comparison of CA vs. SA to be significant in all three cases with CA group having significantly greater mean scores than the SA group. Results are as follows: Avoidance-CA group M=24.15 (SD=4.09) and SA group M=19.44 (SD=5.25, Tukey HSD=3.47, p<.05); Nervous/ Anxious-CA group M=24.96 (SD=6.82) and SA group M=20.40 (SD=6.92, Tukey HSD=5.70, p<.01); Self-Destructive-CA group M=14.87 (SD=4.79) and SA group M=10.47 (SD=6.00, Tukey HSD=3.71, p<.05). All other pairwise comparisons for the three coping strategies were not significant at the .05 level. There were no significant differences among the three types of abuse with regard to Expressive and Cognitive coping strategies.

The following significant results were found for the main effects of Coping Time Frame on coping strategies scores: Avoidance (F1,42=70.53, pNow), Expressive (F1,42= 579.17, pThen), and Cognitive (F1,42=27.52, pThen), and Self-Destructive (F1,42=73.64, pNow). No significant results were found for Coping Time Frame with regard to Nervous/Anxious coping strategies. Further, there were no interaction effects between Type of Abuse and Coping Time Frame on coping strategies.

Discussion

All women in PA and CA groups were physically abused by the family members and most of the sexual abuse was also carried out by the family members in SA and CA groups. These findings coincide with the 2018 national statistics showing that the majority (96.4%-91.7% by parent(s), 4.7% by other relatives) of perpetrators were family members of children with all types of child abuse [33]. The trauma of intercourse along with the physical abuse was inflicted on more women (60%) of the CA group. Abuse began before age 11 for most of the women in SA and PA groups and all of the women of CA group. Most of the participants participated in 12-step groups for alcohol/ drug abuse which coincides with the previous research findings showing that victims of childhood abuse are more likely to engage in alcohol and drug use [6,34]. About two-thirds of drug abuse treatment participants have been found to report being physically, sexually, or emotionally abused during childhood. Also, women who have experienced combined sexual and physical abuse are twice as likely to abuse drugs than those who have experienced sexual and physical abuse separately [35].

As expected, significant differences among the three types of abuse were found for the three emotion-focused coping strategies (Avoidance, Nervous/Anxious, and Self-Destructive) with the CA group having significantly greater mean scores than the SA group on all of the three coping strategies. No significant differences were found among the three types of abuse groups for the two problem-focused coping strategies (Cognitive or Expressive). The CA group showed significantly greater use of the emotion-focused coping strategies because greater the trauma, more emotion-focused coping strategies are used [17]. It has been established that the victims of combined physical and sexual abuse tend to report more unfavorable symptoms because combined abuse is more harmful than even the most severe form of either physical or sexual abuse [36,37].

Avoidant behaviors were used significantly more by the CA group than by the SA and PA groups in the present study. Approach and avoidance are used as the two basic methods of coping with stress and neither mode is viewed as positive or negative by itself. Avoidance can be self-protective and it is a one way not to experience difficult feelings and minimize the emotional impact of being abused [15]. Survivors of childhood abuse tend to feel alienated and perceive themselves as being different from others, which adds to their shame and wanting to keep the family secret about the abuse. There are negative outcomes which sometimes occur when a victim discloses the abuse. Thus, from very early on the victims learn that avoiding disclosure is vital to their survival [38,39].

Anxiety was experienced in higher levels by the combined abuse victims than the physical and sexual abuse separately. The basic outcomes of trauma reported are a sense of helplessness, meaninglessness, and a sense of being disconnected from self and others [40]. In order for a survivor to admit abuse and seek help, a great deal of courage must exist, and this kind of courage is anxiety-provoking. Add to that the knowledge that therapy itself produces anxiety. Individual and group therapy begin to bring man difficult feelings to the surface, thus increasing feelings of anxiety [38,39].

Victims of combined abuse showed more self-destructive behaviors than either sexual or physical abuse alone. It has been repeatedly reported in the literature that persons in treatment for substance abuse and other destructive behaviors are more likely to have experienced childhood sexual and physical abuse as compared to those in the general public [41-43]. One study reported that the adult victims of childhood abuse to be four to five times more likely to abuse alcohol and illegal drugs and twice as likely to smoke, be physically inactive, and be severely obese, compared to those who did not experience childhood abuse [6]. Correspondingly, another study found history of childhood sexual and physical abuse to be highly significant predictors of self-destructive behaviors [44].

Coping Time Frame

There were significant differences between the Then and Now groups of coping time frame for all coping strategies except nervous/anxious. Then mean scores were higher than Now for the two emotion-focused coping strategies (Avoidance and SelfDestructive), whereas the Now mean scores were higher than Then for the problem-focused coping strategies (Expressive and Cognitive). This supports the findings of previous research that coping strategies used early on are emotion-focused and later in adulthood the victims tend to use more problem-solving approaches [45].

Avoidance

The mean score for avoidance was higher for Then than for Now group. The use of avoidant behaviors decreased over time. One possibility for such change is that, the therapists might have affirmed and honored the belief that these “negative” strategies helped early on, but over time they might be hindering the client’s progression form victim to survivor stance. The major issues of trust and self-respect can begin to be addressed and the client can begin the process of reshaping harmful coping strategies into more helpful ones. Avoiding those who abuse you is a healthy strategy in early therapy (and possibly always); while confronting the perpetrators may be a later choice, albeit a nervous/anxious one. Victims use avoidant coping strategies to reduce the negative impact of the stressful event, which is protective and defensive [46]. However, the research has also shown that although the victims rate the avoidant behaviors most helpful, they tend lead to poorer adult adjustment if continued in the long run [47,45].

Self-Destructive

Again, mean score for self-destructive behaviors was higher for Then than for Now. The mean age of the respondents in this study was 39, an age span in which many of the questions which concern the meaning of life begin to surface more than before, and the need to find better ways to exist could be a motivating factor to seek counseling. Through the recovery process, the abuse victim begins to assign a more realistic meaning to the trauma and the ways in which she survived [40]. Also, a large percentage of the respondents were members of 12-step groups, which indicates their need to find more constructive ways to cope with the present. These groups also provide support to bring a more realistic sense of hope for the future.

Expressive

The Now mean score was higher than the Then score for expressive coping strategy. This is consistent with other studies [38,39], which indicates that there are problems encountered by children who disclose their abuse, such as disbelief and blaming the child; but when the abuse is disclosed as an adult, more favorable outcome is experienced. The need for safe attachment seems imperative for recovery from trauma. Roth [47] gave an example of a child who told her mother about the abuse in order to be absolved of some of the guilt and self-blame. When there is no support or protection, it may take years for the survivor to seek help again. Emotional expressiveness is adaptive and increases over time, which is an indication of longterm recovery [16,49]. Non-expressive coping is associated with greater anxiety and depression in former victims of sexual abuse [32]. Wright, Crawford, and Sebastian [18] found those who used cognitive coping strategy of finding positive meaning in the coping process after the abuse experienced less social isolation and better overall adjustment. Silver, Boon, and Stones [49] also found similar results with regard to effective coping facilitated by victims finding some meaning in their victimization. In their study of adult women victimized by their fathers as children who found meaning in their victimization reported less psychological distress and greater resolution of the abuse experience as compared to those incest victims who were still searching for meaning.

Cognitive

The cognitive mean score for Now was also higher than the mean score for Then. Cognitive skills are necessary to reassess the meaning of the trauma and to make some sense out of what happened. In order to cope with feelings of shame, the child must either rebel against authority or try harder to please everyone. The child often feels that she deserved punishment, and the struggle for perfection begins. Research has established that if victims can begin to make some sense out of what happened, they will suffer less distress [38]. In treatment, they may continue to feel distress, but it becomes more manageable.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be considered within the methodological limitations of a small and non-random sample; all subjects were volunteers, raising the possibility that the best or worst adjusted did not volunteer. Some “survivors” may have felt that the trauma was no longer a major focus in their lives, and some victims may have been too fragile to risk opening up to anyone besides their therapist. As compared to combined abuse victims, finding volunteers who were physically abused was very difficult. Perhaps the combined abuse victims were either more prevalent or volunteered more readily.

12-step groups, there were other uncontrolled variables, such as alcohol/drug use, eating disorders, and familial conflict, which might have affected the results as well. Self-reporting and retrospective reporting were also the limitations of the present study. Retrospective recall may distort perceptions of relationships and negative events of childhood [17,50].

In the present study, 93% of the sexual abuse victims were abused by the family member(s) and 40% of these were subjected to the trauma of intercourse. Eighty percent of the combined abuse victims were sexually abused by the family member(s) and 60% of these were assaulted through intercourse. Previous research indicates that the degree of force, the duration of the abuse, and whether the perpetrator was the father significantly affects the long-term adjustment of victims and the forceful intercourse tended to result in greater psychological distress [51]. In the present study the variable of intercourse was not controlled.

Due to the sensitive nature of the research with childhood sexual abuse victims, a random sample would be difficult to obtain, but subjects could be matched on variables such as length of abuse, length of time spent in therapy, presence or absence of intercourse during the abuse, age of participants, participation in 12-step groups etc. As none of the women in this study received treatment at the time of the abuse, a study could be done comparing subjects who had counseling at the time of the abuse and later.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that survivors of combined sexual and physical abuse in childhood tend to use emotionfocused coping strategies (Avoidance, Nervous/Anxious, and Self-Destructive behavior) more than those who had experienced sexual or physical abuse separately. Also, all three types of abuse survivors tend to use problem-focused coping strategies (Expressive and Cognitive) more during their adulthood to cope with their abuse, whereas emotion-focused coping strategies (Avoidance and Self-Destructive behaviors) are used more when the abuse first occurs.

The results of the present study have important implications for treatment of adult women with history of childhood abuse. Understanding the nature and complexity of women’s abuse and their coping strategies over time is a necessary prerequisite for effective treatment. There is an increasing awareness that many adult symptoms are related to one’s past traumas. Reframing these coping strategies which were once considered destructive and relabeling them as protective may neutralize the impact of the past traumas for the clients.

In the present study, the CA group used more Avoidance, Nervous/Anxious, and Self-Destructive strategies than the other groups; yet, all groups used more of these avoidance and selfdestructive strategies in the Then time frame than in the Now time frame, and they used more Expressive and Cognitive skills Now than Then. This seems to confirm the therapeutic need to recognize the approach/avoidance cycle of victims of trauma. Also, learning the language of survivors in describing what is beneficial to them may enable therapists to develop the client’s trust sooner and provide the survivor with confidence to pursue modification of the skills they already possess. The present study adds clarity and importance of identifying the greater impact of combined childhood abuse of women and we recommend that future studies should replicate these findings with males.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023) Adverse Childhood Experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/ violenceprevention/aces/index.html

2. National Children’s Alliance 2021 CAC statistics. https://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/02/NCA-National-Statistics-2021-1.pdf

3. Finkelhor, D. (1984). Child sexual abuse: New theory and research. New York: The Free Press.

4. Demause, L. (1991). The universality of incest. J Psychohistory, 19(2), 123-164.

5. National Center for Victims of Crime (2023) Child Sexual Abuse Statistics. https://victimsofcrime.org/child-sexualabuse-statistics/

6. Felitti, V.J., Anda, R.F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D.F., Spitz, A.M., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

7. Briere, J. (1996). Therapy for Adults Molested as Children: Beyond Survival (Second Edition). New York: Springer Publishing Company 8. Runtz. M,G., & Schallow, MJ.R. (1997). Social support and coping strategies as mediators of adult adjustment following childhood maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 21(2), 211-226. 9. Hall, M., & Hall, J. (2011). The long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse: Counseling implications. http:// counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas11/Article_19.pd 10. Brown, D.W., Anda, R.F., Tiemeier, H., Felitti, V.J., Edwards, V.J., et al. (2009) Adverse childhood experiences and he risk of premature mortality. American J Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 389-396. 11. Springer, K.W., Sheridan, J., Kuo, D., & Carnes, M. (2003). The long-term health outcomes of childhood abuse. J General and Internal Medicine, 18(10), 864-870. 12. Briere, J. (1996). Therapy for Adults Molested as Children: Beyond Survival (Second Edition). New York: Springer Publishing Company. 13. Friedman, L. S., Samet, J. H., Roberts, M. S., Hudlin, M., & Hans, P. (1992). Inquiry about victimization experiences: a survey of patient preferences and physician practices. Archives of internal medicine, 152(6), 1186-1190. 14. Futa, K. T., Nash, C. L., Hansen, D. J., & Garbin, C. P. (2003). Adult survivors of childhood abuse: An analysis of coping mechanisms used for stressful childhood memories and current stressors. Journal of Family Violence, 18, 227- 239. 15. Roth, S., & Newman, E. (1993). The process of coping with incest for adult survivors: Measurement and implications for treatment and research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8(3), 363-377. 16. Burt, M.R., & Katz, B.L. (1988). Coping strategies and recovery from rape Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 528, 345-358. 17. Sesar, K., Simic, N., Barisic, M. (2010). Multi-type childhood abuse, strategies of coping, and psychological adaptations in young adults. Croatian Medical J, 51(5), 406- 416. 18. Wright, M.O., Crawford, E., & Sebastian, K. (2007). Positive resolution of childhood sexual abuse experiences: The role of coping, benefit-finding and meaning-making. Journal of Family Violence, 22(7): 597-608. 19. Cantón-Cortés, D., & Cantón, J. (2010). Coping with child sexual abuse among college students and post-traumatic stress disorder: The role of continuity of abuse and relationship with the perpetrator. Child Abuse & Neglect 34(7), 496-506. 20. Leitenberg, H., Greenwald, E., & Cado, S. (1991). A retrospective study of long-term methods of coping with having been sexually abused during childhood. Child Abuse Neglect, 16, 399-407. 21. Bogar, C.B., & Hulse-Killacky, D. (2006). Resilience determinants and resiliency processes among female adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J Counseling and Development, 84, 318-327. 22. Brand, W, Brand, B., Warner, S.C., & Alexander, P.C. (1997). Coping with incest in adult female survivors. Dissociation, 10(1), 3-10. 23. DiLillo, D.K., Long, P.J., & Russell, L.M. (1994). Childhood coping strategies of intrafamilial and extrafamilial female sexual abuse victims. J Child Sexual Abuse, 3(2), 45-65. 24. DiPalma, L.M. (1994). Patterns of coping and characteristics of high-functioning incest survivors. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 8(2), 82-90. 25. Himelein, M.J., & McElrath, J.V. (1996). Resilient child sexual abuse survivors: Cognitive coping and illusion. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(8), 747-758.

26. Leitenberg, H., Gibson, L.E., & Novy, P.L. (2004). Individual differences among undergraduate women in methods of coping with stressful events: The impact of cumulative childhood stressors and abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28,181-192.

27. Morrow, S.L., & Smith, M.L. (1995). Constructions of survival and coping by women who have survived childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Counseling Psychol, 42(1), 24-33.

28. Perrott, K., Morris, E., Martin, J., & Romans, S. (1998). Cognitive coping styles of women sexually abused in childhood: A qualitative study. Child abuse & neglect, 22(11), 1135-1149.

29. Romans, S.E., Martin, J.L., Morris, E., & Herbison, G.P. (1999). Psychological defense styles in women who report childhood sexual abuse: A controlled community study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(7), 1080-1085.

30. Walsh, K., Fortier, M.A., & DiLillo, D. (2010). Adult coping with childhood sexual abuse: A theoretical and empirical review. Aggression and violent behavior, 15(1), 1-13.

31. Texas Penal Code § 21.01. Definitions. https://codes. findlaw.com/tx/penal-code/penal-sect-21-01.html

32. Gold, S. R., Milan, L. D., Mayall, A., & Johnson, A. E. (1994). A cross-validation study of the Trauma Symptom Checklist: The role of mediating variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9(1), 12-26.

33. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau (2020) Child Maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs. gov/cb/research-data-technology /statistics-research/childmaltreatment.

34. Kendler, K.S., Bulik, C.M., Silberg, J., Hettema, J.M., Myers, J., & Prescott, C.A. (2000). Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of general psychiatry, 57(10), 953-959.

35. Swan, N. (1998). Exploring the role of child abuse in later drug abuse. NIDA Notes, 13(2), 1.

36. Wind, T.W., & Silvern, L. (1992). Type and extent of child abuse as predictors of adult functioning. Journal of Family Violence, 7, 261-281.

37. Higgins, D.J., & McCabe, M.P. (2001). Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and violent behavior, 6(6), 547-578.

38. Lamb, S., & Edgar-Smith, S. (1994). Aspects of disclosure: Mediators of outcome of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9(3), 307-326.

39. Roesler, T.A., & Wind, T.W. (1994). Telling the secret: Adult women describe their disclosures of incest. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9(3), 327-338.

40. Lebowitz, L., Harvey, M.R., & HERMAN, J.L. (1993). A stage-by-dimension model of recovery from sexual trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8(3), 378-391.

41. Makhija, N., & Sher, L. (2007). Childhood abuse, adult alcohol use disorders and suicidal behaviour. Journal of the Association of Physicians, 100(5), 305-309.

42. Briere, J., & Runtz, M. (1986). Suicidal thoughts and behaviours in former sexual abuse victims. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 18(4), 413.

43. Mina, E.E.S., & Gallop, R.M. (1998). Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult self-harm and suicidal behaviour: a literature review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 43(8), 793-800.

44. Van der Kolk, B.A., Perry, J.C., & Herman, J.L. (1991). Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. American journal of Psychiatry, 148(12), 1665-1671.

45. Oaksford, K., & Frude, N. (2004). The process of coping following child sexual abuse: A qualitative study. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 12(2), 41-72.

46. Zak, E.N. (2001). Coping styles, quality of life, and sexual trauma in women veterans. University of North Texas.

47. Leitenberg, H., Greenwald, E., & Cado, S. (1992). A retrospective study of long-term methods of coping with having been sexually abused during childhood. Child abuse & neglect, 16(3), 399-407.

48. Roth, S. (1991). The process of coping with incest. Highland Highlights, XIV, 11-19.

49. Silver, R.L., Boon, C., & Stones, M.H. (1983). Searching for meaning in misfortune: Making sense of incest. Journal of Social issues, 39(2), 81-101.

50. Higgins, D.J., McCabe, M.P. (2000). Multi-type maltreatment and the long-term adjustment of adults. Child Abuse Review, 9(1), 6 -18.

51. Edwards, J.J., & Alexander, P.C. (1992). The contribution of family background to the long-term adjustment of women sexually abused as children. J Inter-Personal Violence, 7, 306-320

Copyright: © 2025 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.